There’s a trou bling bias in how some in the UFO community are reacting to the tragic event involving a veteran who blew up a Cybertruck and left a message claiming China has discovered anti-gravity tech.

bling bias in how some in the UFO community are reacting to the tragic event involving a veteran who blew up a Cybertruck and left a message claiming China has discovered anti-gravity tech.

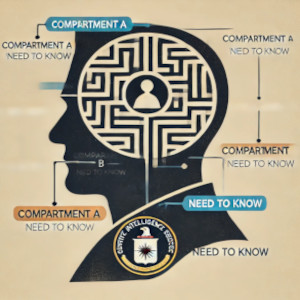

People are latching onto his words as if they hold hidden truths — simply because he’s a veteran. But here’s the reality: not every veteran has access to classified information. Intelligence work is highly compartmentalized. Assuming someone knows “the big secret” just because of their military status is a massive leap in logic.

This isn’t the first time people have rushed to believe extraordinary claims simply because they came from a perceived insider. History is full of examples where credentials or positions of authority were used to legitimize stories that later proved false.

Take Paul Bennewitz, for example. In the 1980s, he was a respected scientist who became convinced that he had uncovered evidence of extraterrestrial activity near Kirtland Air Force Base. Intelligence operatives fed him disinformation to keep him chasing ghosts. His credentials and standing as a scientist gave weight to his claims — but that didn’t make them true. In the end, he suffered a mental breakdown because of the very narrative he had built his life around.

The same mistake happens when people in the UFO community latch onto stories that confirm what they want to believe. Even when there’s a clear context — like someone struggling with emotional distress or PTSD — it’s ignored in favor of the “insider knowledge” narrative.

But here’s what the real story should be:

On average, approximately 16.8 veterans die by suicide every day. That’s over 6,100 lives lost each year to emotional distress and mental health challenges. Since 2001, more than 120,000 veterans have taken their own lives.

Those numbers are staggering — and they should be the focus of our concern.

This veteran’s story shouldn’t be about anti-gravity or World War III. It should be about what we can do to help those who served our country deal with PTSD and regain a sense of normalcy after leaving the service. The focus should be on providing them the support they need to live fulfilling lives, not on chasing sensational claims that only distract from the underlying issues.

Now, ask yourself this:

If the next veteran commits a similar act but leaves a message saying, “There’s no World War III coming, no secret tech, and life is good,” would you accept that just as quickly? Would you latch onto that information with the same conviction?

Or would you suddenly find the context that you’re ignoring now?

The truth doesn’t bend to what we want it to be. Violence and tragedy don’t validate a message — evidence does.

We’ve seen time and time again how dangerous confirmation bias can be. The quest for truth requires discernment, critical thinking, and a willingness to push back against convenient narratives — even when they come from people we’re inclined to trust.

So, before you take someone’s message at face value, ask yourself: Would I believe this just as strongly if it said the opposite?

Because if not, the problem isn’t the message — it’s your bias.

And most importantly, remember this:

If you or someone you know is struggling with thoughts of suicide, please reach out to the Veterans Crisis Line by dialing 988 and pressing 1, or visit www.veteranscrisisline.net for confidential support.